Hemp; a plant for all seasons

03 January 2021

By Grant Gibson - UK-based design, craft and architecture writer and podcaster whose work has been published in The Observer, New Statesman, The Guardian, Daily Telegraph, FRAME, Dwell, House & Garden and quite a few others. A welcome new contributor to Planted’s editorial team.

The thing about hemp is that it sounds too good to be true. After all, this extraordinary plant can be used for a wildly eclectic range of things from bread to buildings, via clothing, car interiors, paint, paper, biofuel and animal bedding. Not only that but it would appear to be environmentally friendly, sequestering carbon, replenishing the soil and killing weeds without the need for chemicals. Potentially it’s also a zero waste crop, meaning the whole plant can be used from stem to flower. All of which begs the question quite; why isn’t it being widely cultivated across the UK?

The answer to that isn’t hard to glean. Despite all its qualities, hemp has an image problem. Put simply, it is too easily mistaken for cannabis. The pair derive from the same species, Cannabis sativa, and contain the psychoactive component THC (tetrahydrocannabinol) but are separate strains that have been developed over the past 10,000 years with contrasting purposes in mind. It’s the kind of nuance that, in recent times, governments have overlooked. As an illustration, farmers wishing to grow the crop have to apply to the Home Office for a license.

However, that wasn’t always the case. During the Tudor reign, for instance, a law was introduced that forced all farmers to give over a portion of their land to cultivating the plant. It was vital both in sails for the navy’s ships (the word canvas is derived from cannabis) and, perhaps as importantly, for rope. In the USA, George Washington mentioned growing the plant in his diary, while other former Presidents such as Thomas Jefferson, Andrew Jackson and Zachary Taylor are also known to have farmed the crop. The American Declaration of Independence is allegedly written on hemp paper, while Levi Strauss made his first jeans from the material.

It’s tricky to explain quite why hemp fell from favour, although there are those that point the finger at large corporations in US with vested interests in materials such as nylon and paper from wood.

However, as the debate over climate change has belatedly become an issue for mainstream politicians, you sense the tide is turning in hemp’s favour. In the US, for example, hemp became legal to grow across 46 states as part of the 2018 Farm Bill.

Meanwhile, increasing numbers of designers and architects are investigating the material’s potential. In Cambridgeshire, Practice Architecture has created the Flat House on Steve Barron’s Margent Farm (pictured above), with a structure made of prefabricated timber-framed cassettes filled with hempcrete. The fact that the hemp itself came from the adjacent fields, provides the project with an even stronger narrative.

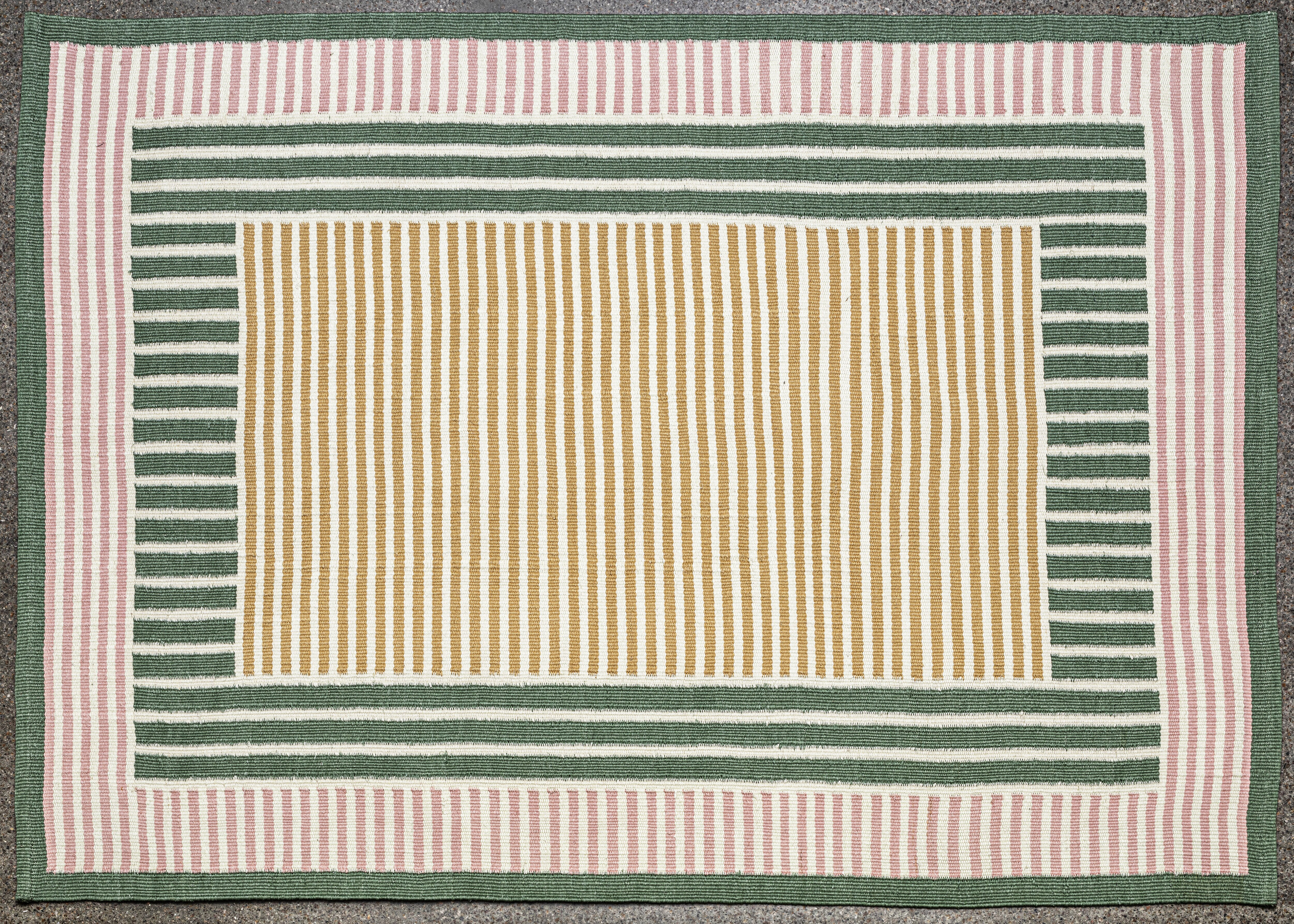

While I was in Copenhagen in the days before the pandemic struck, I was introduced to the work of the up-and-coming textile designer Tanja Kirst. For last year’s Mindcraft Project (which would have opened in Milan during the Salone) she created rugs handwoven with hemp yarn (pictured below). Importantly, every thread consists of 50 thin threads that have been spun together and dyed using bio-colours – meaning she was effectively designing her own yarns. While she could have sourced cheap hemp from China, she elected instead to use an Italian supplier. “As a designer I don’t just want to work with hemp because it’s known for being sustainable,” she said. “I think it’s very important that the process of releasing the fibres from the stem is done in the most sustainable way.”

Interestingly too, she’s keen to work on an industrial scale and has a new collection of rugs made of hemp, and manufactured by Massimo Copenhagen, launching later in the year.

So farmers want to grow the crop and increasing numbers of designers are seeing the material’s potential. There’s a growing market for it as a food stuff and medicine, while CBD oil, derived from the plant’s flower, is becoming increasing popular in treating issues with anxiety (although there is still plenty of room for more research here).

What then is holding it back? The largest hurdle this new – but also paradoxically ancient – industry has to overcome is lack of infrastructure. In other words getting hemp from the field into a usable form for designers and manufacturers. There is a chicken and egg element to this. Tooling requires investment and businesses will only be willing to spend money if they know there’s a market. However, the market won’t grow until the infrastructure is in place. And this is where government needs to step in. Hemp isn’t the answer to all our problems but it might be able to solve a few.

To hear more about hemp listen to Steve Barron talking on the Material Matters with Grant Gibson podcast: grantondesign.com/Steve-Barron

Ends